The Rare 'Buffalo' Nickel That Could Be Worth Thousands Of Dollars

All too often, coin collecting is a squinter's game. Training your eye to spot rare and valuable coins in your spare change might make you some serious money, but it could also seriously damage your vision. Both longtime coin collectors and new numismatists on the block know that the devil is in the details when it comes to finding valuable coins you might have lying around.

Whether combing through piles of coins hidden away like buried treasure, carefully slid into sleeves at coin shows, or documented to within an inch of their metallic lives within online auction webpages, those devilish details can be hard to see. In fact, the only thing standing between a rare coin being worth a fortune or face value could be a missing mint mark, or a barely perceptible doubled die pressing. However, sometimes a valuable coin is so appraised because it bears the mark of something a bit more blatantly obvious — and it doesn't get more obvious than a three-legged buffalo taking a leak.

The coin, part of a series of buffalo nickels produced between 1913 and 1938 by the U.S. Mint, is supposed to feature a portrait of a Native American on its obverse (heads) side, and an image of an American buffalo (or bison) on its reverse (tails) side, with four legs and four clearly visible hooves. However, a mistake at the Denver mint (represented by that "D" mint mark pressed on the coin) erased one of the legs, and added a bit more character.

The story behind the glory of the 1937-D 3-Legged Buffalo Nickel

The 1937-D 3-Legged Buffalo Nickel should be a 1937-D 4-legged Buffalo Nickel. The reasons why it isn't are what makes this coin the talk of the coin-collecting town. A coin is correctly struck when a planchet (a blank piece of metal that will become a finished coin) is stamped by two dies (very hot metal cones) that bear designs for the coin's obverse and reverse sides. However, he story goes (via a 1988 encyclopedia by Walter Breen) that a young Denver mint worker accidentally experienced a clash of the titans, or coin dies, when making this 1937 nickel.

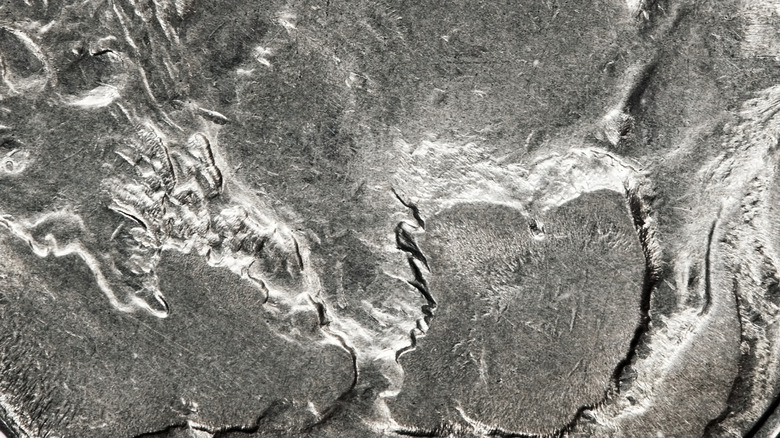

One fateful day, the planchet-feeder stopped feeding blank metal into the press, and the opposing dies crashed together, instead of into a blank planchet. This damaged the dies, which the enterprising young mint worker attempted to fix with a little sandpaper and elbow grease. The young mint worker sanded off whatever imperfections the dies endured in the clash, but perhaps with a bit too much vigor. He rubbed off one of the buffalo's front legs, but still left a visible hoof to that leg behind.

When the "corrected" dies were pressed back into service, the nickels the over-polished, yet damaged dies pressed bore a small (erroneous) raised stream under the buffalo's belly, which might have given coin collectors already giggling about the buffalo's missing leg an idea of why he might have raised it.

Potential coin values and varmints

Error coin collectors have been buzzing about this three-legged buffalo roaming his coin-pressed pasture since first figuring out it actually existed in 1939. Experts estimate that around 10,000 of these error coins entered circulation. Of that number, possibly only a handful of hundreds survive in top-grade condition. Not that cream-of-the-crop totally matters to the deformed die die-hard collectors, of course. The 1937-D Buffalo nickel is a legendary error coin, and collectors might be thrilled to have a very worn edition, or a fine example that has never seen a pocket, so much as a nickel slot.

Coins graded by industry-standard respected outfits like NGC and PCGS have sold for anywhere between $705 and $2,640 at auction. On eBay, a "gem" status of the error coin sold for $5,200.64in December 2024, and in November 2024, a "near-gem" coin sold for $7,522. However, three-legged buffalo nickel buyers beware: while this coin-based buffalo looks like it could break a leg, there are those out there who might fake a leg. Or at least, fake a missing one.

Some fakers go so far as to totally retool coins, which will express itself on the coin as too perfect an imperfection. Others may simply sand off the should-be missing leg themselves. Here's where the squinting comes back into play. When it comes to authenticating this coin, trust professionals, of course — but also know that genuine articles will not have the "P" or "E" in "Pluribus E Unum" touching the buffalo's back, but they will show a bit of a janky hind leg, and of course, the tell-tale raised ridge of relief.