The Real Reason It's So Hard To Tax The Rich

Economic growth: it's been the story of the world since the Industrial Revolution. It's propelled billions of people over the poverty line since 1800 and cut down the distinction between developed and under-developed countries). But alongside the story of growth has been written the story of wealth disparity. The gap in income between rich and poor in the United States has ballooned since the 1970s, and the concentration of wealth at the very top has led many to brand the 2020s a "second Gilded Age." Indeed, the American economy often seems designed precisely to make sure the rich get richer.

Partially as a way to shrink inequality and the resentments that come with it, partially as a funding measure for government, there have been long-standing and loud calls to tax the rich. There are moral, economic, and political cases for doing so — and, not for nothing, it's a popular idea. And yet the top overall tax rate in America has been falling for years. It currently sits at 23%, a far cry from what it was in the post-war boom period.Changing that rate — or dealing with the myriad ways the rich avoid paying what taxes they do owe — is a challenge. Here's why.

The rich have many legal means to avoid paying taxes

It's taken for granted that the rich have ways of wiggling out of their tax bill. They have plenty of ways, and there's nothing illegal about it. Some of the tricks to avoid the taxman are ludicrously simple. For example: many of the richest Americans avoid income tax by not getting most of their money through income. Per Vox, out of $63 million earned in 2023 by Tim Cook, only $3 million of that came from his salary and was therefore subject to income tax. Elon Musk takes no salary at all from Tesla; his pay comes in the form of stock options.

And if a millionaire or billionaire wants to use a portion of their wealth in stock to buy, build, or blow on frivolities, they don't have to sell a single share and pay the tax that comes with the sale. Instead, they can borrow against their assets, often at low interest rates. Even when they do sell stock, they're only taxed on the profit of the sale. And luxuries such as a private jet or a yacht party can always be dressed up as business expenses and treated as a deduction; the rules for what constitutes a business expense aren't exactly ironclad.

Philanthropy delivers tax breaks before any money reaches a charity

The reputation of the super-rich isn't all that of tax-dodging hoarders. Philanthropy has often gone hand-in-hand with wealth, part of the old notion of noblesse oblige. Conveniently, philanthropy also delivers additional tax breaks; donations to a charity can be deducted, and a charity itself is tax-exempt.

Here's the thing, though: per Vox, there's not much in the way of regulations regarding charitable donations. You could find a way to turn your child's school tuition into a deductible donation if you've got a good enough accountant and are shameless enough to flout the spirit of the law while keeping within its letter. Similarly, by donating a work of art, you could end up getting more in a tax write-off than you would by selling the painting (and paying tax on the sale).

But let's assume that a millionaire or billionaire does establish a legitimate charity committed to the public good, or that they pledge a significant amount of their wealth to an existing organization. The deduction on that donation is there for the taking immediately, but the funds don't have to be dispersed in a timely fashion. Through what's known as donor-advised funds (DAF), the super-rich can pool charitable giving into a managed account, which have opaque processes for delivering promised funds to charities in any speedy timeline. In other words: charity waits for benefits, the rich don't.

Taxing the rich hasn't yielded political capital

If taxing the super-rich is a popular idea — and it is — why haven't their rates been raised, or laws passed to close the loopholes the wealthy use to dodge taxes altogether? Well, elected officials have long resisted popular will on the subject. It took two world wars at the beginning of the 20th century to animate politicians enough to raise taxes on the rich, and since the end of World War II, the notion that slashing top tax rates stimulates economies has kept a strong hold over the political class, left and right.

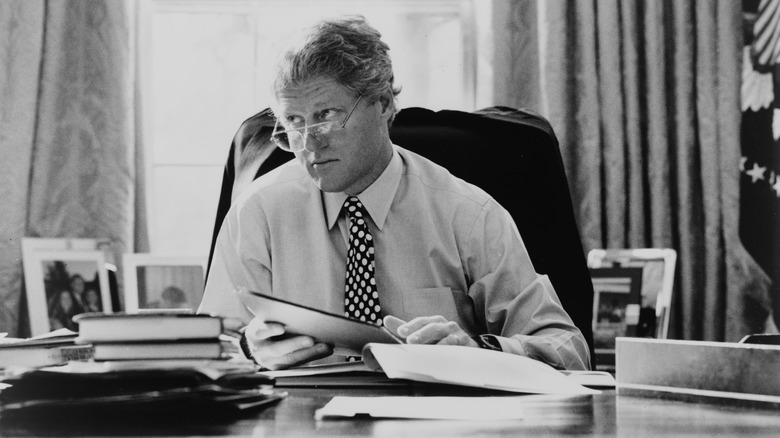

And when some presidents and Congresses have pushed through tax raises on the wealthy, it hasn't paid off for them politically. Such tax increases appear to be one of those issues that's broadly popular but difficult to translate into tangible gains for the political party that takes up the cause. Under the Clinton and Obama administrations, minor tax increases on the rich did not stave off Republican waves in the congressional midterms. And if voters aren't going to reward politicians for enacting popular policies — policies the rich seem determined to get around — why expend political capital on them? Even major postwar disasters haven't been enough to stir moderate politicians to champion the issue of progressive taxation.

The tax debate isn't neatly split along left/right lines

Long-standing caricatures of American politics have the Republican party as the rich man's friend, working to cut their taxes and slash regulations. The Democratic caricature has them as the party of the working class, prepared to regulate and tax the rich. Both images are reductive, and they have shifted in recent years. The caricatures have also obscured nuances and complexities on a number of political issues, tax rates for the wealthy included.

Broadly speaking, it has been the Democrats who have pursued tax hikes on the super-rich, and Republicans who have thrown their weight behind tax cuts and giveaways to the wealthy. But Democrats have leaned into rate cuts for top earners since the Kennedy administration. They've also been resistant to relatively low-hanging fruit for getting tax revenue from the rich: SALT, the acronym used for deductions on state and local taxes. While the Trump administration's 2017 tax cut largely benefited the rich (per Politico), it capped SALT deductions, which meant more tax revenue.

One of the motives behind the SALT deduction was that it most impacted safe Democratic states, which tend to have higher tax burdens to begin with. And since most rich people live in Democratic states, Democrats face political pressure from constituents to resist measures to cap or eliminate SALT deductions.

Wealth taxes have succeeded at the state level

It's not just that the super-rich dodge taxes through legal if shady means. There's a massive and well-funded ecosystem of lobbying and political theory that resists any attempts to shake the status quo. Such efforts are entangled with other conservative priorities, like union-busting, and are often sold as efforts to prevent prohibitive tax hikes on people other than the super-rich — small business owners, for instance. These influence campaigns have long stymied action at the federal level.

But in individual states across America, campaigns to raise taxes on the rich have seen some success in recent years. Per the Center for Public Integrity, Massachusetts went over a century with a constitutionally-mandated flat income tax at 5%, which effectively shifted the tax burden onto lower-income citizens through sales taxes. A campaign for a constitutional amendment won enough signatures to become a ballot measure in 2018, but a court case brought by wealthy backers seemingly killed it. But a fresh push, this time led by the state legislature, got the amendment back on the ballot in 2022. Supporters framed it as "tax justice," and it passed by 4 percentage points, paving the way for an additional 4% income tax on the wealthy.

Across the country, Washington state didn't have to work around its constitution. A bill to move toward a more progressive tax system was put forward in 2021, with the expected revenue earmarked for schools and child care. Not only did it pass, but it generated far more revenue than anyone had expected it to, over $800 million in its first year according to The Seattle Times.