The Difference Between Voluntary Export Restraints And Tariffs (And How It Affects Your Wallet)

Tariffs, tariffs, tariffs — by the end of the 2024 presidential election, it seemed that was the only major point of discussion regarding economics. In the wake of that election, there's been widespread speculation and concern about what a tariff-happy administration might bring about. People are wondering who will bear the brunt of the costs from any tariffs issued by the Trump administration, and the chance other countries might retaliate with tariffs of their own in a trade war.

It's also renewed interest in the nuances of trade and the various mechanisms by which it might be restricted without tariffs, which are effectively taxes on imported goods that increase the cost of those goods for the consumer. If a given country wants a restriction of some kind on an imported good but doesn't want to levy tariffs, they may instead request that the country exporting that good take action to limit trade. The exporting country, if it feels it can accommodate the request and avoid a worse economic deal under tariffs, may offer what's known as a voluntary export restraint (VER): a restriction placed on the exporting of goods to the importing country.

VERs were restricted by the WTO

Voluntary export restraints (VERs) were first employed in the 1930s, and they reached a peak of popularity in the 1980s. They were a favored form of protectionism, an effort by the importing country to protect its domestic industries. Part of its popularity came from the fact that it didn't violate the World Trade Organization's (WTO) General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which aimed to encourage free trade among nations by minimizing or outright eliminating such barriers as tariffs.

But if VERs are accepted within the letter of the GATT, they still seem a departure from its spirit, a fact the WTO came to recognize once the '80s had passed. In 1994, as part of an eight-year round of negotiations known as the Uruguay Round, participating nations agreed to clamp down on such "gray area" devices as VERs. A prohibition on new VERs was established, and existing VERs had a four-year window in which to wrap up.

The WTO did carve out an exception to the VER ban: "An exception could be made for one specific measure for each importing member, subject to mutual agreement with the directly concerned member, where the phase-out date would be 31 December 1999." And with the return of protectionism to international politics in the 21st century, there's been speculation about a comeback for VERs. Some, such as a University of Amsterdam study, feel that current WTO provisions may not be able to prevent such restrictive trade measures.

VERs don't work very well

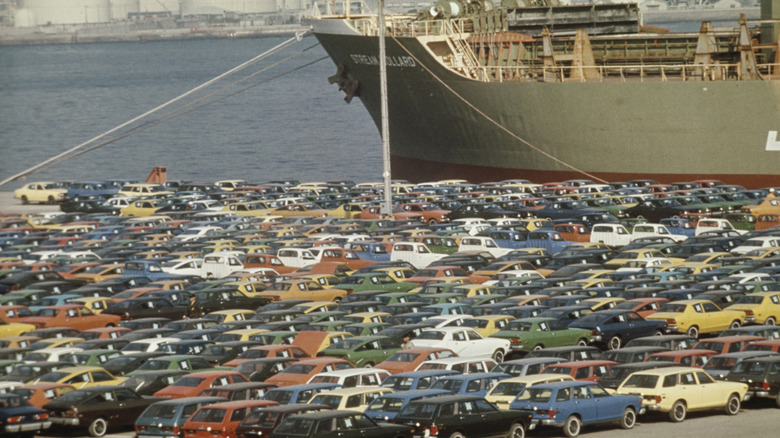

For the average consumer, a voluntary export restraint (VER) is not appreciably different than a tariff; they both increase the cost of imported goods. For nations seeking to protect their domestic industry from foreign imports, the efficacy of VERs is questionable. When Japanese cars threatened the U.S. auto industry in the 1980s, the U.S. pressured Japan to impose a VER on its auto industry. It won American manufacturers a temporary reprieve, and critics of the policy who worried what a VER might do to the economy saw their concerns partially avoided.

But Japanese car companies retained their edge in the American market in two ways. One was to establish a large number of assembly plants within the United States itself. The other, per CFI, was to make up revenue by the type and quality of car they exported. Luxury vehicles with higher price tags could be exported in small numbers, technically adhering to the VER but raking in plenty of cash.