What Even Happened To Blockbuster Video? Here's Why The Company Closed

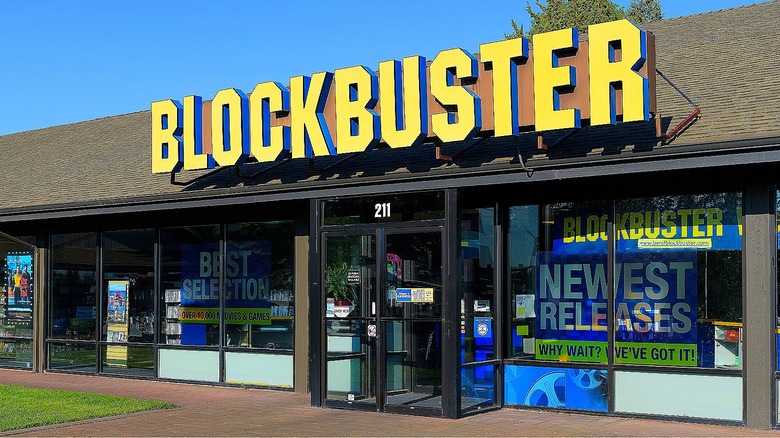

Blockbuster Video was the biggest, brightest of video rental options throughout the '80s, '90s, and early 2000s. However, all that remains today is a lone store that sells nostalgic merch in Bend, Oregon, and online whispers of a dreamed-of return. Blockbuster, once valued at $3 billion, filed for bankruptcy in 2010 and closed its doors on indecisive renters on movie night, right as a little streaming service called Netflix gained steam.

But a switch to streaming wasn't the only factor in Blockbuster's big bust. A decade of disastrous decision-making and a rotating door of C-suite leadership who fought each other over the future is just as much to blame for the death of Blockbuster as a technological paradigm shift. Not to mention, years spent building $900 million in debt making expensive acquisitions of competitors and a failed attempt at taking over another video rental giant, Hollywood Video. Supposedly turning down the purchase of a once-fledgling Netflix for $50 million certainly didn't help Blockbuster, but it is far from the only bad choice the company ever made to safeguard its own longevity.

As Blockbuster's former marketing communications leader, Jonathan Salem Baskin, wrote in a Forbes contributor piece in 2013: "Digital would have changed Blockbuster's business, for sure, but it wasn't its killer. That credit belongs to Blockbuster itself." So how exactly did hubris (not just Netflix) kill the video store?

The drama behind Blockbuster's late fee

From Blockbuster's heyday to its final days, late fees were a major source of controversy, as well as revenue for the company. In 2000, $800 million in late fees accounted for 16% of Blockbuster's total revenue. Throughout the years, Blockbuster leadership played with canceling or increasing late fees to entice customers or pacify investors. The company needed the revenue to operate at a profit, but Blockbuster customers loathed paying these fees, especially at the aggressive rate in which they were charged. Late fees were costly (just like using autopay for subscriptions can be costly); no one wanted a pricey surprise with their movie night.

At times, Blockbuster charged additional rental fees for each day a video or DVD was kept past its due date, sometimes up to $1 a day. Other times, Blockbuster tried to do away with late fees entirely. Or at least say so. Major controversy — and litigation — was brought against Blockbuster in 2005, after the chain advertised an end to late fees. Many customers didn't know the true "No Late Fees" policy: incremental late fees would no longer be charged, but instead the full price for a piece of media would be charged after the first week it wasn't returned.

Forty-seven states sued Blockbuster, and Blockbuster settled (in 2005). Reed Hastings even cited paying $40 in Blockbuster late fees as one inspiration for founding Netflix. Whether that tale is fact or fiction, it touches on how loathed Blockbuster late fees were — and how ready customers might have been for another option. (Read about 13 beloved retail chains that filed for bankruptcy.)

What also went wrong for Blockbuster

Blockbuster leadership was in a state of frequent turnaround, and its CEOs brought very different business philosophies with them with disastrous results. Take former Blockbuster CEO, billionaire Carl Icahn, battling with actual CEO John Antioco in 2005. While Antioco was the CEO who passed on purchasing Netflix, as well as the one behind Blockbuster's "No Late Fees" policy, he was also the champion of Blockbuster Total Access, a channel that integrated the brick-and-mortar Blockbuster store with a Netflix-style streaming app.

Icahn, meanwhile, seemed to think technological advances were just a fad. He bought a controlling interest in Blockbuster, and got representatives sympathetic to his own vision onto the board. Icahn lowered Antioco's yearly bonus, and Antioco decided to leave (in 2007). After, Icahn scrapped Total Access, and helped install new CEO James Keyes. Keyes, like Icahn, seemed to think multimodal streaming was a flash in the pan. As Keyes told Fast Company in 2010 (while denying bankruptcy rumors), renting at Blockbuster was "a lot easier than trying to route movies through my Xbox or Nintendo."

In addition, Blockbuster continued to misgauge what consumers were looking for in a media-renting experience. Instead of ease, low cost, and streaming, Blockbuster focused on bringing in a variety of impulse products like candy and toys to drive revenue. It didn't work — but the memory of packaged Blockbuster cotton candy might live forever in some elder millennial minds, perhaps thought of only when they're clicking around Netflix on movie night.