Does The National Debt Actually Affect You And Your Wallet?

The national debt is an oft-talked about subject. From the real-time National Debt Clock (showing a total debt of over $35 trillion as of September 2024) to the debate stage, the subject has long been a hot-button issue in which politicians (who also talk about taxes, one feature that's intimately related), pundits, and average citizens all talk about how the national debt is a looming issue in some way or another. Some financial advisers like Dave Ramsey suggest that all debt is bad, but there's a distinct difference between the national debt and personal repayment obligations that might factor into your own personal finances.

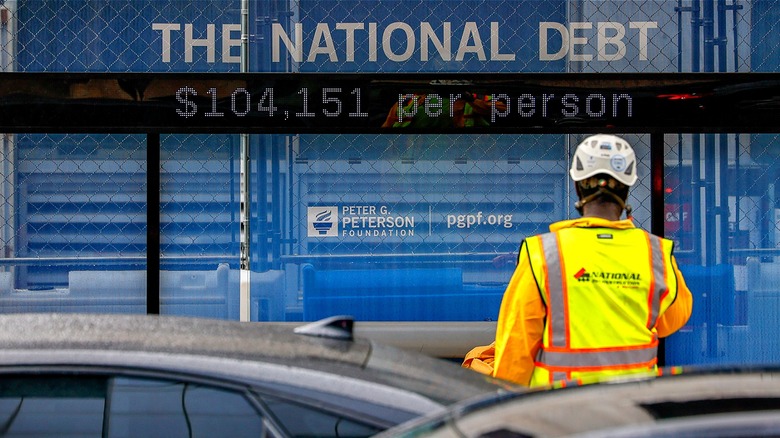

Firstly, even though the debt clock shows a "debt per citizen" figure of nearly $105,000, no one in America will ever actually have to pay any of this. In one sense, talk about the country's debt burden is somewhat sensationalized. The national debt has become a trigger point for political conversations more broadly, with government shutdowns occurring occasionally over a contentious debate among politicians on how to piece together an agreeable budget that reaches far enough across the aisle — both directly and over debt-ceiling legislation.

However, this said, there are certain real consequences to brushing the issue off as non-important. While it can be hard to fully appreciate what the national debt means to the typical American, it can introduce alarming woes to the American wallet if given the right conditions to really metastasize.

The national debt doesn't tend to affect Americans' daily lives

In a 2012 Vlogbrothers explainer, John Green (of the Crash Course library of educational videos, among other claims to fame) notes that while the U.S. national debt is quite a daunting figure, "the plurality of that debt is actually owned by us. Us being American individuals and institutions."

The Peter G. Peterson Foundation measured that value at 79% of the nation's total debt in 2023. To this, Green added yet another caveat. "It's important to note that the U.S. also owns foreign debt," he said. The ratio is actually fairly equitable, too; for every dollar of debt owed, the U.S. owns roughly 89 cents of foreign debt. What's more, while a creditor might be able to take you to court to retrieve funding loaned to you, foreign countries and bond arrangements don't have this option. National debt obligations can't simply be called in by the owner, thus making these tangled networks of borrowed capital relatively stable arrangements between governments and across the American public.

Generally speaking, when the federal government needs to raise funds to tackle a new project or maintain routine spending needs, it sells bonds. These are offered with guaranteed maturity values. Per the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 10-year bonds dropped to an interest rate of 3.87% as of August 2024 (from 4.25% in July). With rate cuts in the works now, the present is perhaps a good time to invest in these assets, before they fall in value. Though bonds don't provide the same upside potential as other investments, they're rock-solid. You'll get back the principal plus a pre-agreed interest addition with every bond that comes to maturity.

But prolonged interest-rate heat can create spiraling trouble

As an investment driver (the more money the government needs, the more attractive bonds tend to look to investors), the national debt as it relates to bond sales is the primary means of influence over the typical consumer's wallet. However, there are other factors to consider. While a growing national debt isn't the massive crisis that some might hope to frame it as, this doesn't mean it's something to simply dismiss, either.

Rising interest rates, an issue that the American public has faced in the years since the pandemic's outbreak, can make managing the debt less sustainable over the short term. This leads to one of two approaches in combating fiscal strain, and neither are particularly palatable. For one, the government can print more money, feeding fuel to the inflationary fire in an effort to tamp down consumer panic in the short term. For example, while many consumers celebrated pandemic stimulus payments, the long-term effects of this infusion of cash into the U.S. economy are still being felt at the grocery store, in the housing market, and at the gas pump.

The alternative to this is to reduce spending — sometimes called "austerity." This might seem less drastic and more closely resemble the approach to consumer finance. Yet, the federal government has ensured access to all manner of public goods, things that demand money to operate. Services like highway maintenance, Medicare coverage, K-12 education, and Social Security payments (here's more on Social Security's continued solvency in the future) are funded through tax collection and the federal budget. Prolonged rate hikes could ultimately reduce services, fuel inflation, or raise taxes under the most extreme conditions.