Labor Day: Its History, How It Became A Holiday, And Why We Celebrate It

For many Americans, Labor Day is their last big hurrah of the summer. On the first Monday of September, with no work or school on the schedule, family and friends unite to enjoy pools, beaches, barbecues, and other fun, warm-weather festivities that are about to come to an end until next year's Memorial Day. In fact, many go all-out for their Labor Day celebrations, with 41% of Americans spending up to $199 on the holiday, according to a 2024 study by GOBankingRates.

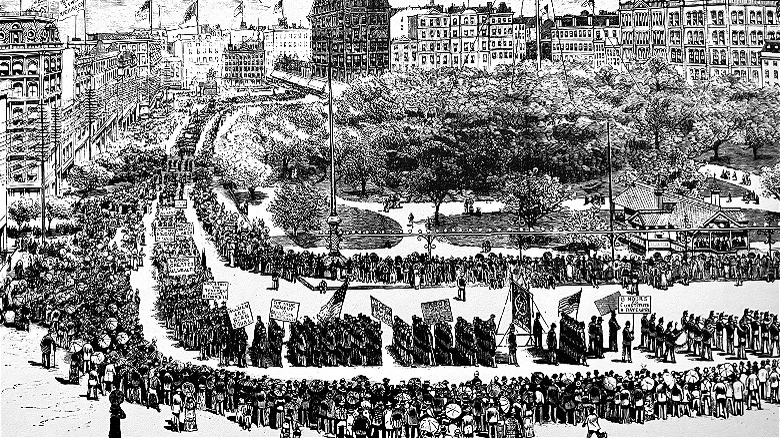

Yet, as folks sip on their seltzers and soak in the rays, free from their professional obligations, the reason why they get to enjoy such a leisure-filled day each September might not be considered. This luxury — among many others when it comes to modern-day working conditions — is all thanks to a group of union workers who, in 1882 in New York City, used their collective voice to bring about massive, necessary changes for the employed.

The first Labor Day

Working nine-to-five can oftentimes seem both draining and monotonous, especially if you don't particularly love your job (though finding this one thing can make you happier at work). However, workers of the late 1800s would've accepted that 40-hour workweek in a heartbeat. At the time, it was common for employees of the manufacturing industry — both adults and young children — to work 70 hours over a span of six days a week in cramped and badly ventilated spaces. Yet, even with these long hours, many families were still unable to live comfortably due to the poor pay (on that note, here's what to do if your employer doesn't pay you today).

Finally, though, in 1882, a group of workers decided that enough was enough. On September 5, in New York City, the Central Labor Union rallied approximately 10,000 workers to march from City Hall to 42nd Street and take part in street parades, picnics, and more. It became the United States' first Labor Day. The purpose of the day was to showcase the unified strength of the city's working individuals and recognize their contributions to the country's economy. That first gathering in New York would serve as the catalyst for workers across the U.S. to push for better conditions, pay, work-life balance, and overall recognition, with unofficial marches taking place in other states as well.

How Labor Day became a holiday

In February 1887, Oregon became the first state to make Labor Day an official public holiday, with Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York following suit that year. The number of official state Labor Days would grow to over 20 between 1888 and 1894, the year Congress proposed a bill to make Labor Day (the first Monday of September) a federal holiday. President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law on June 28.

"Though the [federal] law only made Labor Day an official holiday for federal workers, over time, the holiday spread to all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories," explained the U.S. Department of Labor, adding, "... And it now applies to all state and local government employees. Private employers generally recognize the day as a holiday, too."

The passage of the law also kickstarted more in-depth conversations about working conditions in America, which steadily improved. Henry Ford doubled worker wages to $5 in 1914, and, in 1926, implemented the first nine-to-five workday and five-day workweek. The year 1938 saw the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act, which Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law on October 24. The new law required paid overtime to any worker putting in over 40 hours a week.

And so, as you enjoy the beach and burgers on Labor Day this year, keep in mind the holiday's history as well; specifically, the people who made this celebration, and the elimination of the 70-hour workweek, possible.