The Dark History Of Tipping In America

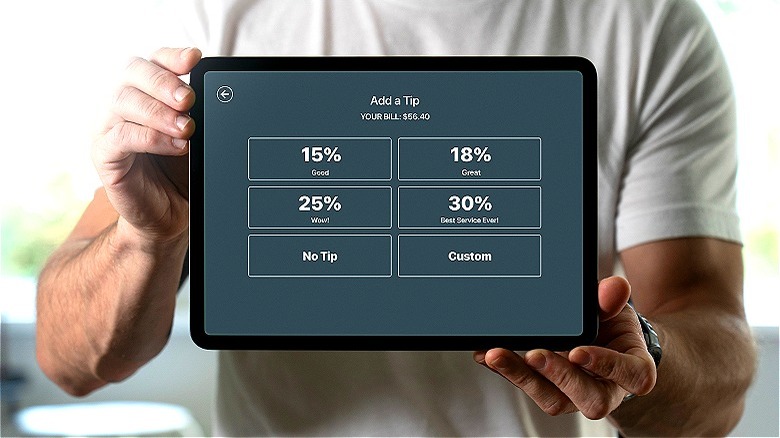

In the post-pandemic economy, tipping has increasingly become a sticking point for consumers. In fact, according to a 2023 Bankrate survey, 66% of Americans now have a negative view of tipping altogether. Similarly, the consistency of how often people tip has been steadily declining, with 66% of Americans reporting that they always tip in 2023 compared to 77% in 2019. As Ted Rossman, a Bankrate industry analyst said, "Few topics elicit as many passionate opinions as tipping. There's so much confusion regarding who to tip, and if so, how much." What's more, generational differences in tipping have also affected tipped employees, many of whom rely on tips to offset low non-livable wages.

Yet, the modern-day tipping economy that surrounds the food industry in America is a unique one among first-world nations. Even while Americans first experienced the premise of tipping in Europe, most European countries today don't mandate a socially expected tip and, for those who choose to tip, the amounts are significantly lower than in the U.S. So how did American tipping culture get so removed from European tradition? Even worse, how did American tipping become a necessary and relied-upon element of wages for an entire class of workers struggling to pay the bills? While tipping was originally rooted in a European master-serf classicism tradition (in which a servant could earn additional money for performing above and beyond their duties), ultimately the modern-day U.S. practice is inextricably linked with the country's history of slavery.

The origin of tipping in America

You might be wondering when tipping started in the United States and by whom? According to Time, the answer is the wealthy. Specifically, wealthy Americans who traveled abroad in the 1850s and 1860s and experienced the tipping tradition while vacationing in Europe. Despite foundational American principles that generally objected to the aristocratic nature of Europe, these wealthy travelers ultimately wanted to appear more aristocratic so they began replicating the tradition once they were back in the U.S. as a way of seeming more cultured. However, public sentiment toward tipping was swift and entirely unsupportive with some even deeming it "offensively un-American." Critics claimed tipping violated the anti-aristocratic ethic of America, despite the fact those who initially introduced it aimed to, in fact, be thought of as aristocratic.

The anti-tipping movement was so strong that the attitude actually spread all the way back to Europe where it lasted. This is, in large part, why Europe doesn't have the expected tipping culture today that the U.S. does. However, the anti-tipping movement ultimately struggled to keep up its momentum in the U.S. in the face of companies who saw new ways to offset their labor costs. Stephen Zagor, a professor at Columbia Business School, explained to CNBC that "economically, companies really liked the opportunity to not have to pay for labor." Lobbying on the part of businesses, and later on, corporations, helped to ensure that any legal pushback to tipping was ultimately quashed.

Tipping took root post-slavery

While the outcome of the Civil War, and the eventual constitutional amendment that followed, formally ended the institution of slavery in America, it didn't end the oppression of Black Americans. Notably, there was a lack of economic or administrative support for those who were newly freed, which allowed many to be wrongfully taken advantage of. Companies, in particular, saw a financial opportunity in taking advantage of the labor of these typically under-educated and low-income people.

In fact, the job opportunities available to newly freed slaves were extremely limited (and typically very low-paying), with the only real options being sharecropping and working as servants. With this in mind, there were, technically, a few customer-facing jobs available to freed slaves, such as a waiter or a railroad porter. However, these specific positions are a big part of the tipping culture we have today. You see, working as a waiter or railroad porter often required freed slaves to agree to not be paid by their employer.

The agreement was, instead, that guests would tip these workers to make up their wages. This removed the burden of companies paying their own employees and instead placed the responsibility of supplementing a worker's income on to customers. As Saru Jayaraman, director of the Food Labor Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley explained to Time, "These industries demanded the right to basically continue slavery with a $0 wage and tip." The one industry, in particular, that really drove the institutionalization of tipping that we still experience today was, unsurprisingly, the railroad industry.

Pushback against tipping in America

While employers hoping to offset labor costs ultimately won the war against abolishing tipping, the battle to get there was still a long affair. Also, while the general sentiment against tipping was largely viewed as purely economical, it's impossible to remove the racial bias and classicism attached to many Americans' views of tipping. For instance, in 1902, the journalist John Speed wrote, "Negroes take tips, of course, one expects that of them — it is a token of their inferiority. But to give money to a white man was embarrassing to me." This further hurt Black workers who were already paid less, or not at all, compared to their white counterparts.

Pushback continued when William Howard Taft (who had been dubbed the "patron saint of the anti-tip crusade") became president of the United States in 1908; by 1918, seven states (Arkansas, Georgia, Iowa, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington) had passed anti-tipping bills, making it illegal to either give or receive tips. However, by that point consumers had moved away from the anti-tipping movement. Instead, tipping grew among consumers, helped in large part by the lobbying of corporations and employers looking to keep their labor costs low, and it ended up being impossible to police something so widespread. There was also a growing knowledge that not tipping could lead to negative, or even vengeful, service. Therefore, by 1926, all the anti-tipping legislation in the seven states that banned it had been repealed as tipping won out in America's culinary experience.

Tipping in America today

There are several key worker-specific laws that have further fueled the tipping culture we have in America today. For starters, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (which established the premise of a minimum wage) excluded food service from the covered industries. Then, in 1966, the "tip credit" was created by Congress, which introduced the concept of a sub-minimum wage for tipped workers that mainly affected the restaurant industry. This not only further perpetuated the will of employers to offset labor costs directly onto consumers, but also pushed tipped workers into even more financially strained positions. The tipped minimum wage has — and continues to — perpetuate the acceptability of taking advantage of the country's most disadvantaged workers.

However, consumers in recent years have grown more aware of the abusive labor policies at play with the perpetuation of tips. The aforementioned Bankrate survey found that 41% of U.S. adults feel that businesses should be paying their employees better rather than relying on tips from customers to offset wages. However, until policy change is made, this has only served to push consumers to lessen their tips. There has also been a significant shift in who, exactly, people are supposed to tip. From tipping food-delivery workers to Uber drivers to baristas to self-checkout machines, there seems to be no limit to who (or what) consumers are expected to tip (or not) today. Understandably, this has contributed to a renewed negative sentiment toward tipping that ultimately hurts the workers who need tips the most.

Wages for tipped employees

There are several states in the U.S. that still use the "tip credit" to pay employees significantly less than the (already low) federal minimum wage. This sub-minimum wage allows employers to pay their workers less than the federal minimum wage, with the understanding that the rest of the wage will be "made up for" via tips from customers. This means that servers, bartenders, and any other tipped positions are being paid the federal tipped minimum wage of $2.13 (it's worth mentioning that this amount hasn't changed since 1991). Sixteen states still use this sub-minimum wage for tipped workers, while another 26 states (and the District of Columbia) have tipped minimum wages that are technically higher than $2.13 but are still below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. For example, Maryland's tipped worker hourly rate is a whopping $3.63.

Eight states (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Montana, Minnesota, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) have eliminated the tipped wage entirely and allow their own state or federal minimum wage to apply to all workers, regardless of whether the job includes tipping. A large population of restaurant service staff across the country live on the poverty line (which makes tipping so important), but the states with a true minimum wage (as opposed to a sub-minimum tipped wage) are changing that. According to the Economic Policy Institute, 7% of restaurant workers in states where they earn the minimum wage are on the poverty line versus 18% of restaurant workers in states with sub-minimum wages.